Two federal tax provisions meant to boost company research—the Research and Experimentation (R&E) tax deduction and the Research Tax Credit—are often conflated. Adding to the confusion, the research activities supported by both provisions are often referred to interchangeably as “research and development (R&D)” or “research and experimentation (R&E).” Either R&D or R&E are acceptable in popular usage; the important difference lies in the distinction between the deduction or the credit.

Deductions take effect before a corporation’s taxes are calculated and lower taxes indirectly. Corporations subtract (deduct) their expenses from their revenues to determine the profits they’re taxed on. The more they can deduct, the lower their taxable income, and the less they owe in taxes.

In contrast, tax credits take effect after a corporation’s taxes have been calculated and directly reduce how much they have to pay—often reducing their tax liability dollar for dollar.

The Research and Experimentation (R&E) Expensing Tax Deduction

The research and experimentation (R&E) expensing tax deduction provided by Section 174 of the tax code allows companies of any size to deduct the cost of qualified research expenses from their profits before calculating their federal taxes owed. Before 2022, firms could choose to deduct all qualifying expenses in the year incurred.

Beginning in 2022, thanks to one of the few revenue-raising provisions of the 2017 Trump-GOP tax law, companies will need to deduct their research costs more slowly, spreading the deduction out over a 5-year period for domestic research and a 15-year period for foreign research. This reduces the value of the deduction, increasing companies’ taxable income and requiring them to pay more in income taxes upfront.

Changing the R&E tax deduction to permanently allow corporations to write off their research expenses all at once would cost roughly $200 billion over 10 years.

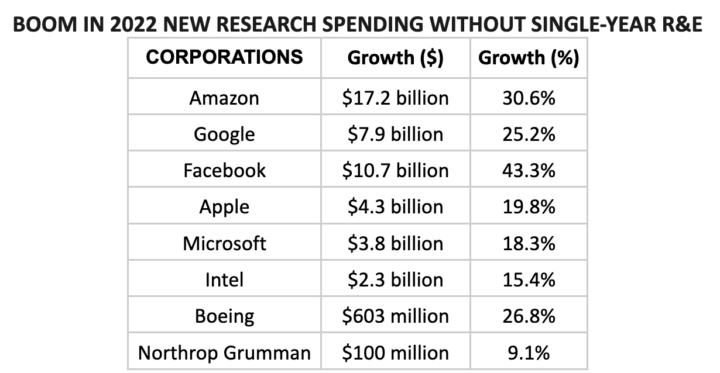

There is no evidence that spreading out the cost of R&E deductions has any effect on corporations’ decision to invest in research. In fact, since the 5-year R&E rules came into effect in 2022, there has been an explosion of new research spending by major corporations. If the new R&E rules were having an adverse effect on their capacity to finance research, we would have expected to see the opposite.

Source: Americans for Tax Fairness Analysis of Corporate 10-K

Source: Americans for Tax Fairness Analysis of Corporate 10-K

The Research Tax Credit

In contrast, the research tax credit provided by Section 41 of the tax code and made permanent in 2015 is a nonrefundable, dollar-for-dollar general business credit that can be used to offset a company’s final tax bill. Like the expensing deduction, companies of any size can take advantage of the research tax credit so long as they have qualifying research expenses above a certain base level.

Experts estimate that in 2022 alone, corporations received as much as $35 billion in R&D tax credits—a 550% increase since 2001, outpacing both the growth in company-funded research and GDP. Hugely profitable corporations Google, Apple, Intel, Microsoft, and Boeing each received billions of dollars through the R&D tax credit in the 5-year period between 2018-2022, not counting any federal tax subsidies they received through the research expensing deduction.

But even as U.S. taxpayers subsidize research at these billion-dollar companies through the permanent tax credit, these corporations have lobbied hard for even more. Notably absent from many of their letters to Congress in support of R&E expensing is any acknowledgement of the billions they receive through the permanent credit.

Furthermore, some of the most prominent firms lobbying for special treatment for corporate research costs are also among the nation’s most prominent tax dodgers. Two corporations on the Leadership Committee of the R&D Coalition paid only a fraction of the 21% corporate tax rate in place from 2018 through 2020: Northrop Grumman paid only half (10.5%) on its $12.4 billion in profits and Amazon paid just 4.3% on its $43.4 billion in profits. Another committee member, Boeing, paid a tax rate of just 5.4% from 2008 to 2015 when the statutory rate was 35%, completely zeroing out its tax liability in five of those years.

**Changes to the Research Tax Credit Included in the Inflation Reduction Act

Most firms use the R&D tax credit to offset their income taxes, but a subset of small startup firms are allowed to use the credit to offset their payroll expenses instead. Under the Qualified Small Business Payroll Tax Credit for Increasing Research Activities—a subsection of the Section 41 R&D tax credit—a startup firm with a larger R&D tax credit available than they have in income tax liability can use the remaining credit to pay the employer portion of the FICA tax. (Note that employees must still pay the employee share of FICA taxes.) This payroll tax offset is targeted at true start-ups: companies can only use it in a year in which they have less than $5 million in revenue (not profits) after five years of no revenue at all.

Prior to 2023, businesses could offset no more than $250,000 in payroll taxes and only Social Security taxes. The Inflation Reduction Act enacted last year by President Biden and Democrats in Congress doubled that limit beginning this year to $500,000 and allows it to be taken against Medicare taxes as well.