Major corporations enjoying record profits from low tax rates and inflated prices are lobbying Congress to renew three major tax breaks before the end of the year, two that expired this year and a third expiring next year. These tax giveaways—which could cost $600 billion in lost revenue if extended over 10 years—were given expiration dates by Republicans as a way to hide the true cost of the 40% tax-rate cut they gave corporations in 2017. Now Republicans want to keep the tax-rate cut and retain the special tax breaks, making the Trump-GOP tax law even more of a boondoggle.

To avoid the sticker shock of a full 10-year renewal, corporate allies in Congress are seeking to extend the tax breaks for just one or two years, exploiting timing gimmicks that make the extensions seem relatively cheap. Because of the nature of tax advantages they offer, two of the breaks that together cost more than $400 billion over 10 years appear relatively cost-free in their first few years when using standard scoring procedures.

But that is an illusion: members of Congress are merely biding time with short-term proposals, patiently awaiting an opportunity to make the tax breaks permanent. Such an opportunity for a permanent extension could arise in the next Congress, especially in a GOP-controlled House, as they seek to renew the Trump-GOP tax cuts expiring in 2026.

Congress should not be reversing corporate tax increases that were included as deliberate pay-fors in the 2017 Trump-GOP tax law. Instead, it should be moving in the opposite direction: building on the tax reforms in the Democrats’ Inflation Reduction Act enacted this year and in President Biden’s original Build Back Better plan so that the biggest firms pay closer to their fair share of taxes.

The corporate-tax giveaways likely being pushed in this year’s lame duck session are:

- Reversing the change in the Research & Experimentation tax deduction so that corporations can continue to write off 100% of research expenses all at once instead of more realistically over five years. Cost: $60 billion (1st year*); $155 billion (10 years).

- Reversing the change in the Net Interest Deduction tax break so that corporations can continue to deduct more of the cost of borrowing money by changing how the deduction is calculated. Cost: $20 billion (1st year); $200 billion (10 years).

- Extending 100% Bonus Depreciation beyond 2023 so corporations can continue to write off immediately the full cost of assets that hold their value a long time. Cost: $15 billion (1st year*); $250 billion (10 years).

*As noted above, the 10-year cost of a 1-year extension will appear to be less costly than it is, because official scorekeepers must pretend that the tax break will lapse after the first year, making tax collections for later years artificially appear higher. If R&E and bonus depreciation deductions are taken immediately, for example, they aren’t available to be taken the next year, making it score as though there’s little change in any given company’s tax liability over the full 10-year window. But if history is any guide, Congress will repeat these short extensions indefinitely, wiping out all of the offsets in later years.

Congress should oppose these corporate tax giveaways:

- In 2017, Republicans gave corporations a massive 40% tax-rate cut in the Trump-GOP tax law. To partially offset the costs of that giveaway they included a few business tax increases, which they and their corporate allies now want to repeal. Congress should not support making the Trump-GOP tax cuts even more of a boondoggle. The latest CBO estimate of the cost of all the unpaid for tax cuts in the Trump-GOP tax law during their first decade is $1.6 trillion, with most of those cuts benefiting corporations and the wealthy.

- For years corporations have been enjoying record-high profits while paying record-low taxes. It’s time for them to start paying their fair share, not to get more breaks. Corporations that would benefit from extension of these breaks include the nation’s biggest and wealthiest: Amazon, AT&T, Bank of America, FedEx, Ford, General Motors, Google, Intel, Microsoft, Netflix, Northrop Grumman, UPS, Verizon and Walt Disney.

- Working families need the revenue that fairer corporate taxes would generate to lower the costs of household essentials. Greater corporate tax revenue can help lower the cost families pay for healthcare, education, housing and other vital services; strengthen Social Security and Medicare, which Republicans have threatened to cut; and fund other useful public services.

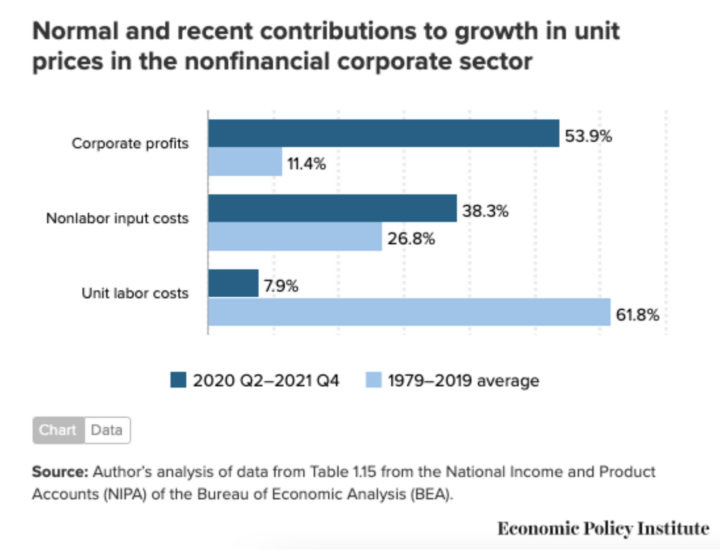

- Swollen corporate profits are responsible for over half of the growth in the cost of goods since 2020, according to an Economic Policy Institute analysis. Price-gouging corporations should not be further rewarded with more tax cuts.

- The 2022 midterm elections offered no mandate for corporate tax cuts—in fact, the message delivered by the electorate was just the opposite. While several factors contributed to the GOP’s poor showing in the midterms, more money was spent on tax issue ads in congressional races than on any other issue in the two months before the election, with 71% of it by Republicans and their outside groups. Those ads attacked Democrats mostly for the tax increases in the Inflation Reduction Act—the top one being the 15% Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT). Voters rejected this anti-tax-fairness agenda; it should not be supported in Congress’s closing days.

- The public overwhelmingly supports increasing taxes on corporations so they pay their fair share. That support was reflected in the rejection of fear mongering on taxes in the midterms. There were many important issues driving the election, one was the popularity of the components of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which raises taxes on the biggest corporations and promises a crackdown on rich and corporate tax cheats.

- Renewing these tax breaks undercuts a major reform in the Inflation Reduction Act—the 15% Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax. The CAMT requires the roughly 90 U.S. corporations that earn at least $1 billion in average annual profits over the previous three years to pay a 15% minimum tax rate on their “book” income, which is usually lower than “taxable” income because it allows fewer deductions. But corporations will still be able to deduct depreciation and R&D expenses, deductions that will be made more generous by these proposed tax breaks.

Corporations Are Posting Record Profits as Their Tax Payments Plummet

The 2017 Trump-GOP tax law handed U.S. corporations a 40% cut in their income-tax rate, slashing it from 35% to 21%. That tax-rate giveaway has added to corporate profits that were already racking up records even as working families struggled to pay household bills.

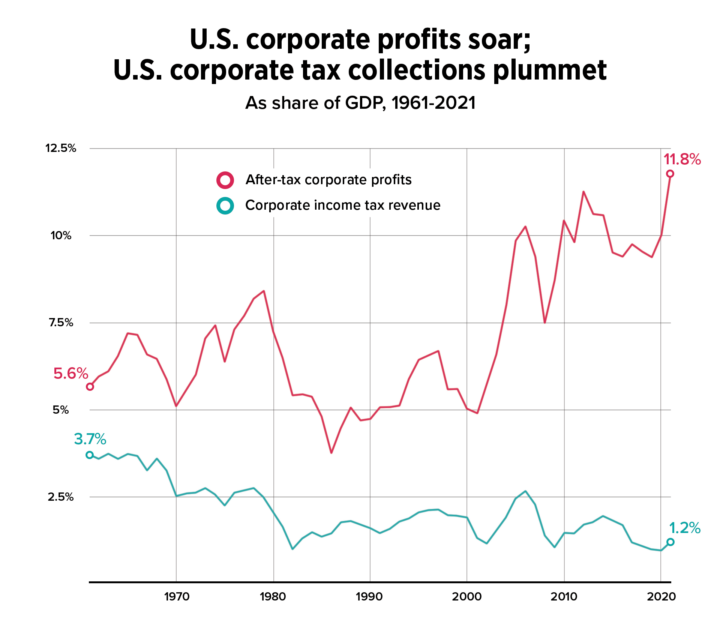

Corporate profits as a share of the economy have never been higher—11.8% of GDP in 2021—even as corporate tax payments have rarely been lower—just 1.2% of GDP the same year. [Figure 1]

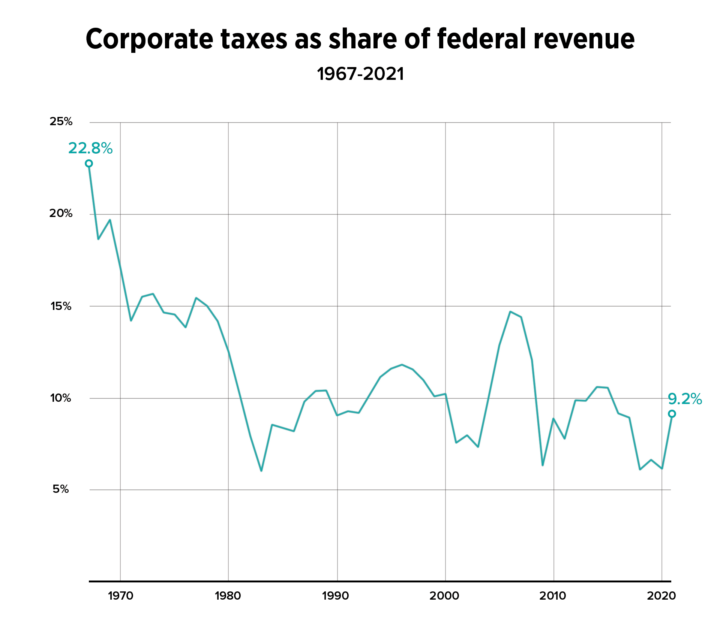

Corporations contribute far less in federal revenue than they did in the 1970s, when corporate taxes provided nearly one quarter of all revenue. Today they provide about 9%. [Figure 2]

The American people have a right to and a need for the revenue that higher corporate taxes would generate: to pay for public investments that would lower the cost to families of healthcare, education, housing and other vital services; to strengthen Social Security and Medicare, which Republicans have threatened to cut; and for other important purposes.

Corporations Are Charging Consumers Higher Prices—They Should Pay Higher Taxes

The pandemic helped spark inflation worldwide, but big corporations have exploited the crisis to jack up their prices and their profits. According to an Economic Policy Institute analysis, swollen corporate profits are responsible for over half (54%) of the nation’s price increases since 2020, which is not normal. Between 1979 and 2019 it was higher labor costs that mostly caused higher prices, but that has not been the case during our pandemic-induced inflation. [Figure 3]

Rising wages aren’t even keeping pace with skyrocketing prices. Big firms can get away with charging so much because they have few competitors left after decades of business consolidation.

As a result, in early 2022, U.S. corporations enjoyed the highest profit margins in more than 70 years, fueled by price gouging that far outpaces the firms’ own rising costs. That followed record annual profits in 2021 of $2.8 trillion, up 25% from a year earlier.

Higher taxes on corporations would recover some of the money that consumers have been forking over in inflated prices. That increased tax revenue could then be used to lower the costs working people pay for healthcare, childcare, housing and other services.

Corporations Don’t Pay Enough in Taxes Now

Huge, profitable corporations often pay lower tax rates than teachers, truck drivers and nurses. The average American pays about a 13% federal income-tax rate. By comparison:

- In 2018, the year after passage of the Trump-GOP tax law, over 1,500 U.S.-based multinational corporations together paid an average U.S. tax rate of just 7.8%.

- Some billion-dollar corporations pay nothing at all. For 2020, 55 big firms—including FedEx, Nike and Salesforce—paid zero federal income tax, despite over $40 billion in combined profits. For the three years 2018-20, 39 corporations—including FedEx and Salesforce again, T-Mobile and others—paid nothing in federal income taxes, despite over $120 billion in combined profits.

- In 2021, Amazon, Exxon Mobil, Microsoft, Verizon and more than a dozen other corporate giants each paid a federal income-tax rate of less than 10%.

- Internationally, U.S. corporate tax revenue as a share of the economy ranks 36 out of 38, among the countries that make up the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

To remedy this injustice, the Inflation Reduction Act included a 15% minimum tax on corporations with at least $1 billion in average annual profits over the previous three years. The minimum tax will be based on the profits firms boast to Wall Street to attract investors, rather than the lower numbers they generally report to the IRS, which can result in no taxes owed despite being profitable.

A major reason corporations pay so little in taxes now (measured as a share of the economy) compared with past decades is the 40% income-tax-rate cut provided by the 2017 Trump-GOP tax law. To partially pay the cost of that huge rate cut—most of the cost was added to the deficit—the GOP trimmed the three corporate tax breaks discussed in this analysis. But the law delayed the implementation of those revenue-raising changes for four to five years so that future Congresses would have a chance to later delay or cancel them—precisely what some members are proposing to do now.

EXPLANATION OF THE POSSIBLE CORPORATE TAX CUTS

Research & Experimentation Tax Deduction: Writing Off Research Expenses All at Once Instead of More Realistically Over Time

Businesses subtract costs from revenue to determine their taxable income. Some expenses are for items—like wages and office supplies—that get used up immediately or nearly so. It makes sense to deduct their full cost in the year paid. But other items—like buildings and equipment —last many years, so it’s more accurate to write off only a portion of the expense each year.

Corporations have two ways of reducing their tax bills for research and development (R&D, also known as research and experimentation, or R&E) expenses: a tax credit, which directly reduces a firm’s tax liability and is calculated as a percentage of certain amounts spent on research; and a tax deduction, which lowers taxable income and therefore indirectly reduces taxes due. The 2017 Trump-GOP tax law made no changes to the tax credit, but it substantially reformed the tax deduction to give corporations their deep tax-rate cut. Starting this year, corporations have to start writing off R&D costs over five years instead of just one year.

Having made this tradeoff in 2017, corporations and their allies in Congress now want to go back on the deal by keeping the big tax-rate cut in place while also allowing businesses to once again immediately write off R&D costs. They even want to change the law retroactively, so that businesses that had already begun the process this year of deducting R&D over time would be allowed to instead take the full deduction in 2022, cutting their tax bill. It makes no economic sense to provide handouts on the tax bill they will pay in 2023 for business decisions that have already been implemented in 2022. That’s the definition of a giveaway at the expense of other taxpayers.

Allowing for a 100% deduction for R&D costs in 2022 would cost $60 billion in lost tax revenue, according to one independent analysis. If this tax break were made permanent, it would cost $155 billion over 10 years.

The House-passed Build Back Better Act would have extended this tax break for four years and paid for it by raising over $800 billion in new taxes on corporations, while lowering the cost of essential services to American families. In contrast, making the R&D tax break permanent without raising new taxes on corporations risks undoing the critical gains in tax fairness that Democrats achieved in the Inflation Reduction Act.

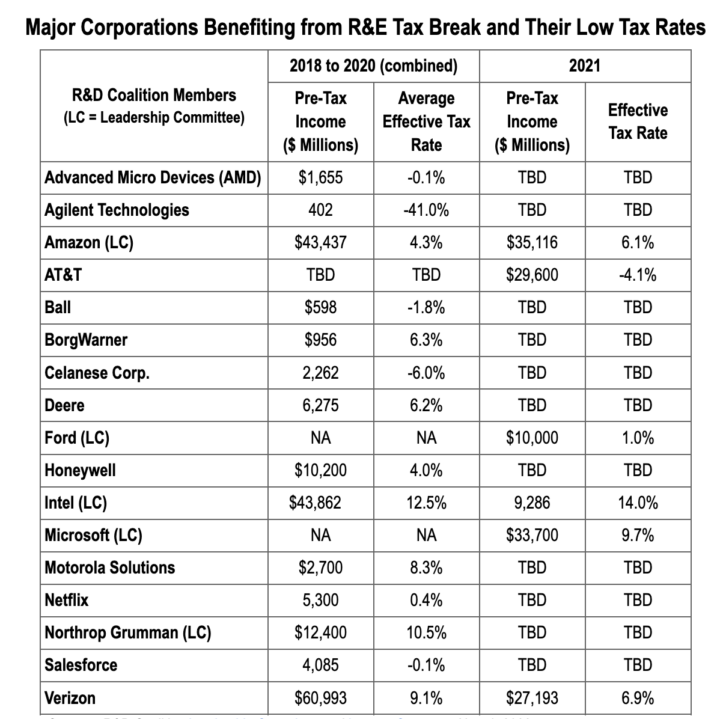

Many of the firms at the forefront of the effort to restore this tax break pay some of the lowest corporate tax rates. Five members of the leadership committee of the R&D Coalition—Amazon, Ford, Intel, Microsoft, and Northrop Grumman—which is leading the charge for this tax break, have in recent years paid tax rates below the average 13% rate paid by families. [See Table] The R&D deduction was one of the tax breaks that helped them avoid paying their fair share.

Sources: R&D Coalition Leadership Committee and letter to Congress, Nov. 4, 2022

ITEP Corporate Tax Avoidance 2018-2020, Jul. 20, 2021, and Twenty-Three Corporations Saved $50 Billion So Far Under Trump Tax Law’s “Bonus Depreciation” that Many Lawmakers Want to Extend, Nov. 2022

CAP: These 19 Fortune 100 Companies Paid Next to Nothing in Taxes, Apr. 26, 2022

Net Interest Deduction Tax Break: Deducting a Bigger Share of Interest Costs by Raising a Limit on How It’s Calculated

The interest that businesses pay on loans is an expense they can deduct from their earnings before figuring their income taxes. The Trump-GOP tax law limited the amount businesses can deduct to 30% of a certain common measure of their income (there are different ways of calculating this figure) as a way to make their corporate tax-rate cut look less costly.

Starting this year, the Trump-GOP tax law further reduced the value of this deduction by changing the method for determining this measure of income so that it winds up smaller. From 2018 to 2021, the deduction for business interest expense was limited to 30% of a corporation’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). Beginning in 2022 the deduction was limited to 30% of earnings before interest and tax (EBIT). Having to subtract depreciation and amortization costs before determining the limit leads to a smaller earnings figure and therefore a smaller amount of deductible interest.

Republicans and some Democrats want to go back on this deal, too, by allowing businesses to calculate income in the original way, making their interest deductions larger and therefore their tax bills smaller. Once again, they want to make the change retroactive, so that corporations already prepared to figure their interest deduction the new way in 2022 would be allowed to return to the old way.

The cost is $20 billion for a one-year, retroactive resurrection of this corporate-tax giveaway. But corporations and their congressional allies really want a permanent restoration of this special break, which would cost $200 billion over ten years.

Private equity—groups of rich people who buy businesses—is focused on preserving the net interest deduction tax break through its trade association, the American Investment Council. They have been lobbying for passage of the Permanently Preserving America’s Investment in Manufacturing Act (S.1077/H.R.5371). It would make the more lucrative method of determining deductible interest permanent. AT&T is also a major promoter of this tax break.

There are numerous U.S. private-equity billionaires and they and other wealthy investors already enjoy huge tax loopholes, including the 20% tax rate on capital gains and carried interest. They don’t need more tax breaks like reversion to the previous, more generous method of determining interest deductions.

100% Bonus Depreciation Tax Break: Writing Off Immediately the Full Cost of Assets that Hold Their Value a Long Time

Among the corporate handouts in the 2017 Trump-GOP tax law was the ability to write off in the year of purchase 100% of the cost of assets lasting up to 20 years—known as “bonus depreciation.” This gratuitous gift to corporate America is scheduled to start shrinking in 2023, when only 80% of the cost of such purchases will be immediately deductible. The share is scheduled to decline by 20 percentage points a year until it disappears in 2027.

Some of the biggest and most profitable corporations in America are lobbying to make the 100% bonus depreciation tax break permanent. Delaying the date when this tax break begins to wind down until 2024 would cost $15 billion, but making it permanent would cost $250 billion.

Corporations have long benefited generously from accelerated depreciation, which allows the cost of business assets such as buildings, machinery, cars and trucks to be written off faster than the assets actually wear out.

But the 100% bonus depreciation tax break under the Trump-GOP law supercharged accelerated depreciation between 2018 and 2023. It’s no surprise corporate lobbyists are pushing hard to save it: accelerated depreciation is often the largest component of their clients’ tax avoidance strategy and writing off an asset’s full cost the year it is bought is the fastest acceleration of all.

According to a recent report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 23 of the nation’s biggest corporations avoided a combined $50 billion in taxes because of accelerated depreciation over the first four years (2018-21) of the Trump-GOP tax cuts, when 100% bonus depreciation was in effect. Among them:

- Amazon: $78 billion in profits; 5.1% effective federal income tax rate

- Bank of America: $108 billion in profits; 3.8% tax rate

- FedEx: $11.6 billion in profits; 1.5% tax rate

- General Motors: $24 billion in profits; 0.2% tax rate

- Google: $145 billion in profits; 11.8% tax rate

- Intel: $53 billion in profits; 12.8% tax rate

- J.P. Morgan Chase: $140 billion in profits; 10.5% tax rate

- United Parcel Service: $23.3 billion in profits; 12.4% tax rate

- Verizon: $88 billion in profits; 8.4% tax rate

- Walt Disney: $33 billion in profits; 7.7% tax rate

For many firms—including famous names like Amazon, FedEx, and UPS—accelerated depreciation was solely responsible for their tax savings in those four years. Extending 100% bonus depreciation would add to the costs of the Trump-GOP tax cuts and create an additional loophole that will undercut the goal of the 15% Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax.

More than 121 House Republicans and 17 Senate Republicans are sponsoring the ALIGN Act (H.R.2558 / S.1166) to make the Trump-era bonus depreciation rules permanent. This legislation is backed by Verizon and AT&T, which have lobbied heavily for the bills over the past two years. As noted above, Verizon has paid just an 8.4% effective federal income tax rate over the last four years on $88 billion in profits. In 2021, AT&T reported $29.6 billion in profits but an effective tax rate of negative 4.1%.

Corporations and their allies in Congress claim tax breaks like accelerated and bonus depreciation boost business investment, but tax analysts make the case that corporations would make these investments anyway even in the absence of the tax breaks to ensure they are more competitive and thus more profitable. Research has shown that corporate executives seem to not focus on accelerated depreciation when they are deciding whether to make new investments; that is more the interest of corporate tax departments that are focused on maximizing profits by exploiting tax loopholes.

Congress Should Raise Corporate Taxes Instead of Cutting Them

Below are a few potential corporate tax reforms that Congress should be pursuing rather than considering corporate tax cuts. These are all based on proposals made the past two years by President Biden, the House Ways and Means Committee or included in last year’s House-passed Build Back Better Act.

Raise the Corporate Income Tax Rate

President Biden proposed raising the corporate income-tax rate to 28%—half way back to the 35% rate in effect five years ago, before Republicans slashed it to 21%. Partially restoring the corporate tax rate would not put U.S. firms at a disadvantage because the corporate tax levels of all of our international economic rivals are less than ours. The corporate income tax is one of the fairest ways of raising revenue because it largely comes from shareholders, who are overwhelmingly wealthy.

During the crafting of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan in the House last year, the Ways and Means Committee voted to increase the rate to 26.5%. The full House would have voted on and likely approved that rate as part of the Build Back Better Act they sent onto the Senate, but it was taken out of the bill before it reached the House floor because of Sen. Sinema’s (D-AZ) opposition.

Biden’s proposed rate increase to 28% would raise $858 billion over 10 years. The 26.5% rate would raise $540 billion.

Close Offshore Corporate Tax Loopholes

One of the most successful ways that the biggest corporations dodge taxes is by shifting profits and operations offshore. The tax code actually encourages this practice because, under current U.S. law, the foreign profits of American firms are taxed less than their domestic profits are: the domestic corporate tax rate is 21%, while the effective tax rate on foreign profits is 10.5% (scheduled to increase to 13.125% in 2026). This corporate profit shifting costs the federal government an estimated $60 billion in lost tax revenue every year.

President Biden, leading Senate Democrats and others have all proposed reforms that would keep U.S. profits and jobs here in America and raise as much as $1 trillion in corporate tax revenue over 10 years. The House passed more modest reforms in 2021 as part of the Build Back Better Act, which would have raised $300 billion.

Strengthen the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax

The main reason profitable public corporations can pay such low tax rates is that they can essentially calculate their profits two ways. One version (“book earnings”) produces high profits the firms can flaunt on Wall Street to attract investors; the other (“taxable earnings”) allows them to minimize their profits to the IRS to avoid taxes.

The Inflation Reduction Act began to narrow this loophole by forcing the nation’s most profitable corporations—those earning at least $1 billion in average annual profits over the previous three years—to pay at least 15% of their book earnings in taxes. But it’s estimated that just 90 corporations will be covered by this new minimum tax, leaving thousands of profitable public firms free to go on escaping taxes through this accounting loophole.

Closing loopholes in the law would make it applicable to many more corporations and raise an extra $90 billion over 10 years. Among those loopholes are the continued ability to write off excessive amounts of depreciation and research expenses when figuring the minimum tax (which costs $55 billion in lost revenue); and an exemption from the tax for private equity firms if none of the companies they own individually earn over $1 billion, even if the combined profits of all the firm’s companies exceed that threshold ($35 billion).

Additional Resources

Americans for Tax Fairness: Backgrounder on Push for End-of-Year Corporate Tax Breaks & Retirement Plan Tax Breaks Benefiting the Wealthy

Center for American Progress: Child Tax Credit Improvements Must Come Before Corporate Tax Breaks

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy: Congress Should Not Leave Children Out of Possible Year-End Tax Deal

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy: Twenty-Three Corporations Saved $50 Billion So Far Under Trump Tax Law’s “Bonus Depreciation” that Many Lawmakers Want to Extend